Spending a billion dollars is too hard.

Key Takeaways

You cannot responsibly spend a billion dollars in one lifetime. Even with private jets, four homes, full-time staff, and $50 million a year in charitable giving, the fortune keeps growing.

Extreme wealth isn’t liquid, it’s power. Billionaires rarely hold cash. Their wealth is locked in assets designed to appreciate and avoid taxation, which makes it nearly impossible to shrink their fortunes through spending alone.

The system isn’t broken. It’s doing exactly what it was built to do. Capital gains are taxed less than income. Philanthropy can erase tax bills. And billionaires can pass on massive wealth while contributing very little to the public systems that support everyone else.

A billion dollars is too much money for one family to spend in a lifetime. I spend a lot of money by most people’s standards but even me, lover of boutique hotels, golf travel, and under-the-radar designer shoes, and starting businesses would struggle to come up with enough stuff or companies to buy and experiences to have to start cutting into my billion-dollar nest egg.

As a financial advisor, I’ve done financial plans for people with millions of dollars, even tens of millions of dollars. These are business owners who sold at the right time, tech employees with equity windfalls, and folks who gain access to millions when they lose a parent. But I’ve never done a financial plan for a billionaire.

So I decided to try.

What would it look like, practically speaking, if you had so much money you couldn’t even figure out how to spend it? What do the numbers actually say? How much can one family reasonably consume before things start to get absurd?

Spoiler alert: A billion dollars is too much money. It can’t possibly be spent in a lifetime. All the private jets, yachts, private islands, real estate, and jewelry in the world just barely start to make a dent in a billion-dollar nest egg.

My imaginary family, headed up by patriarch Billy Onaire, only has one billion dollars. Well, that’s today. As you’ll see in the financial plan below, even after spending wildly and giving away millions, the billion-dollar nest egg just keeps growing on its own.

Most Billionaires Don’t Have Cash, They Have Control

Practically speaking, billionaires aren’t sitting on billions of dollars of cash. Their wealth resides in real estate portfolios or within publicly traded companies, usually in the company they helped build. For this exercise, I imagined a client with $1.36 billion in total net worth, most of it tied up in Alphabet (Google) stock. I chose Google because it doesn’t pay a dividend to shareholders. So in order for our billionaire family to live off their nest egg, they would need to sell some of their Google stock each year. But, as I talked about in Part 1, most billionaires can’t or don’t want to sell their concentrated stock positions because they will lose control of their companies. So, let’s imagine a scenario when the Onaire family has been rich for a while. They sold some Google stock previously and moved it to a more diversified equity and bond portfolio. They also have some real estate and hold $50 million in cash, you know just for petty everyday expenses.

My imaginary billionaires are in their early 40s. They are married, have two kids, and live well. They want to be generous, but they want to know what is actually possible. How much money can they give away? They are currently giving away $10 million annually, but they came to me, their financial planner, to ask if they could go up to $50 million.

In case you missed Part 1…

How to be a Good Billionaire Part 1: There Shouldn’t Be Billionaires

If you want to be a good billionaire, pay more taxes.

You Can’t Actually Spend a Billion Dollars

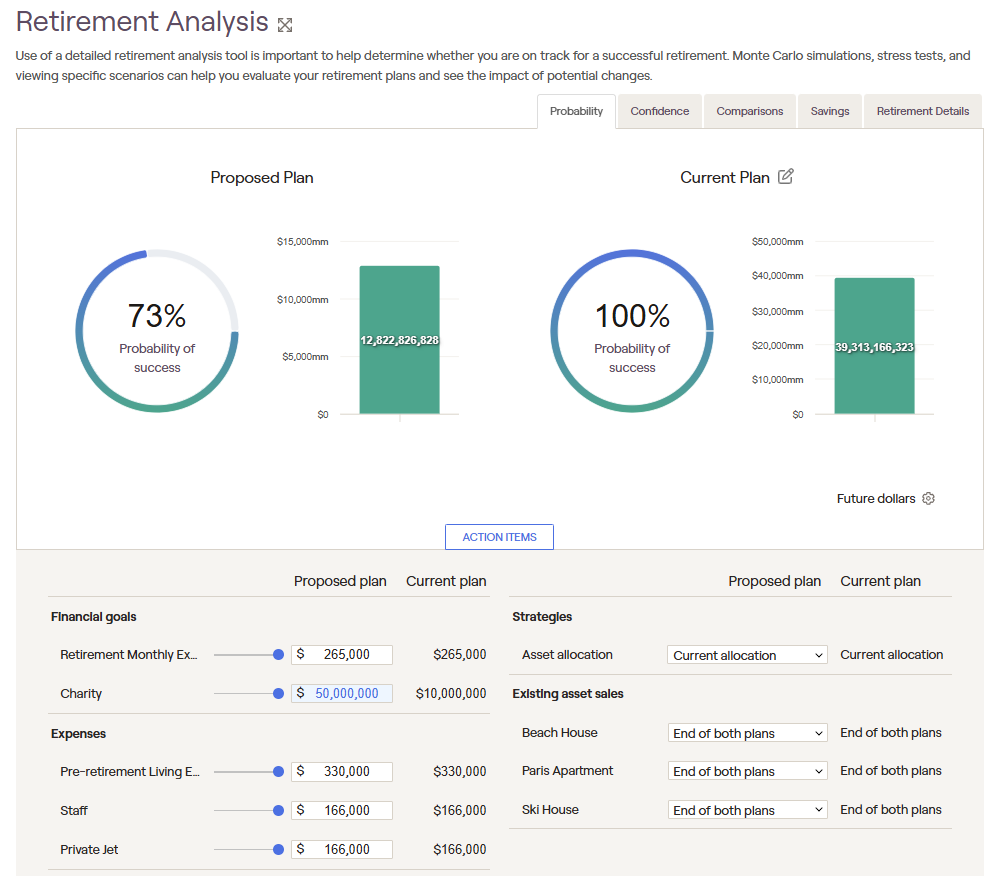

I ran their numbers through Right Capital, the software we use at Brooklyn FI to help clients plan for their futures. It’s a neat, powerful, little tool that takes in our clients’ current financial picture and forecasts it out into the future. Short of knowing the future, it’s a pretty good indicator of what might happen to their money based on thousands of different outcomes.

This exercise is basically to tell us if the client is going to run out of money and when if they keep up their current lifestyle. Are their savings and spending habits balanced? After looking at that, we add in their wants and needs to further test the strength of the financial plan.

Right Capital’s retirement tool runs thousands of simulations based on market behavior, inflation, taxes, and spending patterns. It’s called a Monte Carlo simulation. The result is a confidence level, or, the percentage of scenarios in which you don’t run out of money.

For normal people, 85% is a solid number to shoot for when you run a Monte Carlo simulation. That means, through market turmoil and recessions, most of the time (85%), they will end their plan with enough money to live on.

But for the Onaires? Even with the extravagant spending of maintaining four properties, the confidence level of the simulation is a perfect 100%.

I thought this exercise would be fun for me. I was imagining all the things I would buy if money was truly unlimited. Sure, flying private would be luxurious and convenient. I’d spend tens of thousands of dollars on hotels and golf trips. I’d buy stuff like vintage Jaeger-Le-Coultre watches. I’d collect 1960s Jaguars and 1970s Porsches. I’d make a great billionaire. I’d be a classy as hell billionaire. I’d throw Gastby-level parties all the time. I’d be generous with my friends and family. But at a certain point, after I added in the cars and the jets and the $50,000 a month in imaginary expenses for “entertainment,” the absurdity sunk in. Even just doing this thought exercise was exhausting. I’d think, “Well, if I’m going to have a vintage car collection, I need someone to manage it. If I’m going to have multiple properties all over the world, I need a staff to manage it. Oh, and I probably need lots of assistants, lawyers, advisors, and people to manage all my stuff.

Sounds like a logistical nightmare.

Before I got into finance as a career, I struggled with understanding how numbers apply to real life. Numeracy is the equivalent of the word “literacy,” but for numbers. It means: can you understand how math applies to real life?1

And while my numbers in this thought exercise aren’t perfect, they are certainly eye-opening. Can you imagine how much money a billion dollars is? A billion dollars is 1,000 million. It’s also 100,000 ten-thousands. If you’ve ever stressed over a $10,000 tuition bill or a $10,000 credit card balance, imagine having enough money to cover that not once, not a hundred times, but a hundred thousand times. A billion dollars is such a large number that we forget what it actually is: more money than most people could responsibly spend in ten lifetimes.

But, let’s try.

Billy Onaire and his brood spend $2 million a year on household staff and another $2 million on a private jet.

They spend $330,000 total per month, including:

$50,000 on cars and transportation

$50,000 on utilities

$25,000 on dining out

$50,000 on entertainment

$166,000 on household staff

$166,000 for a private jet

They own four homes worth $42.8 million: a primary residence, a ski house, a Paris apartment, and a beach house.

And still, their money grows. By the time the wife dies at 104, their projected net worth is $39 billion.

Compound interest loves billionaires.

Let’s look at the numbers.

Next year, with their living expenses and donating $50 million to charity, they have a negative cash flow of $116,529,393.

But look! Despite that, their net worth actually goes up, because of their investments. Google is a high-performing stock, but consider this: the interest alone on the $50 million they have in cash sitting in the bank would earn them $2,165,000 per year. (Note, that I used today’s effective federal funds rate of 4.33%.) That’s a lot of money. Their $50 million dollar cash position is still only 5% of a billion dollars! That just blows my mind.

Reader, I spent hours and hours working on this financial plan. It was fascinating. My financial planner brain had so many ideas about how to shield their income from taxes, but I toned them down to keep this simple.

Ready to Get Mad? They Pay 15.9% Income Tax

That’s right. Because our patriarch Billy only takes a modest salary from Google of $150,000 for his family of four, the effective federal tax rate is 15.9%. But he’s only paying 10% income tax at the federal level, the rest is capital gains tax on the Google stock they have to sell to pay for their lifestyle2. For comparison, my personal effective tax rate is more than triple that because my income comes from my business and my husband earns W2 income.

That fucking sucks.

The reason why: they give so much away in charity that it reduces their federal tax burden. When Billy dies at age 90, you can see the tax rate shoot right back up because they stop giving to charity (there are other factors that I don’t have enough space to get into).

But here’s where it just kills me. The Onaire family essentially pays a flat tax on capital gains of 20% their entire lives. That’s just absurd. Compare that to a lawyer working 70 hours work weeks making $700,000 a year in salary and bonuses. That lawyer will hit the top tax bracket of 37% which starts at around $600,000 making their effective tax rate about 30%. This lawyer works their ass off but only gets to keep 70% of what they make. Hopefully the power of investing is starting to sink in. I hope that lawyer is able to save 20% of their income into a diversified portfolio!

A Tax Proposal That Would Actually Matter

If society is going to continue to function, tax policy has to be reformed. There is simply too much money at the top and not enough of it is being invested in infrastructure.

Here’s my modest proposal (read more in last week’s post (LINK)

Keep the 20% capital gains rate for almost everyone

But if someone realizes over $50 million in gains in one year, tax the excess at 50%

This only touches the very top. It doesn’t affect retirees, founders with modest exits, or the average investor. But it starts to treat extraordinary windfalls like what they are: opportunities to return something to the public.

For our hypothetical family, poor lowly billionaires with just over one billion dollars, they would need to sell at least $100 million in stock each year to support their spending and charitable efforts.

Oh, and by the way, this family isn’t selling Google stock, paying the tax, and then making the donation. They are simply donating the appreciated stock to the charity of their choice and getting the full tax deduction. The qualified charity (let’s say it’s Unicef), as a 501c3, doesn’t have to pay tax when they sell the stock to fund their cause. So effectively, that profit from owning Google is never, ever taxed. (Please note I’m oversimplifying this to make my point. The nuances of taxes, capital gains, and charitable gifting are extremely complex.)

Even Philanthropy Can’t Save You From the Math

To test the upper limits of giving, I built a new version of the Onaire’s plan. In the “Proposed Plan,” they:

Donate $50 million per year

Leave $25 million per child

Keep all four homes, the private jet, and their current spending

The result?

They still die with $12 billion. And their confidence level is a strong 73%.

That’s how much money this is. You can fly private, fund a foundation, and give millions away every year, and your portfolio growth still outweighs it all.

This isn’t about someone being too greedy or not generous enough. It's about a tax system that has let capital grow tax-deferred and under-regulated for decades.

The System Isn’t Broken, It’s Working Exactly as Designed

That’s the point. This isn’t a fluke. This is the intended outcome of decades of policy.

We made it easier to accumulate wealth than to earn it. We made it easier to pass it on than to share it. And we made it possible for a billionaire to spend like a Roy, give like a Gates, and still grow their fortune.

This isn’t about envy. It’s about power. And whether that power should sit quietly in a family office or help fund the world we all live in.

But I don’t think this system is producing good outcomes or good people.

We love to ogle billionaires and one brilliant example is the fictitious Roy family in HBO show Succession. In the very first episode, the Roy family takes helicopters to a remote field to play a friendly game of softball. Roman Roy offers a young boy, the son of the groundskeeper, a million dollars if he can hit a home run. It’s a joke to him. It’s the perfect character setup of this depraved, and out-of-touch rich kid. The boy, maybe ten years old, steps up to the plate and gives it everything he has. He makes it to third base. Roman tears up the check.

Everyone laughs.

The boy walks away empty-handed. The family goes back to brunch.

It’s a small scene, but it says everything. Money becomes performance. Power is something to dangle. Human dignity is a footnote. And even when a promise is made, even when the stakes feel life-changing to someone else, the billionaire walks away unchanged. It’s a sickening scene, but such a perfect example of the result of when the top 1% have so much and the rest have so little.

Tax the Rich

This exercise wasn’t just about spending. It was about scale. It was about putting a number (one billion dollars) into human terms and realizing that there’s no version of personal consumption or philanthropy that can responsibly absorb that kind of wealth. The fortune grows faster than you can offload it.

At a certain point, the absurdity of the math becomes the point. It shows how wildly disconnected extreme wealth is from the realities of everyday life. It proves how broken the system is, not because billionaires are bad people, but because the rules are built to make hoarding inevitable.

If this is what one billion dollars does, imagine what happens at ten. Or a hundred.

You cannot spend your way out of being a billionaire.

But you can tax it.

And maybe, just maybe, we should.

Parting shot: If you can buy four homes, a private jet, give away $50 million a year, and still die with $12 billion, something is broken.

The best $20 I spent this week: $20 on Enchiladas Suizas at the newly revamped Kellogg’s Diner.

David Brooks wrote an excellent and alarming piece in the New York Times last week about how literacy and numeracy rates have declined so much and made us all so stupid that we got these idiotic tariffs. Read it, it’s great.

In reality, many millionaires and billionaires don’t actually sell their stock, they just borrow against it.

This was a fascinating read AJ! Thanks for going down this rabbit hole for us.

GREAT read. I actually ran a Monte Carlo on myself in Fidelity (your tool is far better it looks like). It told me I will die at 90 years old with $43M in the bank. I'm wealthy - but not that wealthy. I retired at 48 with a healthy portfolio of stocks and I trade and manage my portfolio. I absolutely LOVE your newsletter and I paid an effective rate last year of close to 28% based on 20% capital gains and the self employment tax that I have to pay based on my newsletter and podcast. I'm a big fan so keep up the great work.

Gary